Download a PDF copy of the Lighthouse Wealth Management Outlook: April 2025

In light of the recently implemented (and constantly updating) tariff measures, we have modified our typical quarterly update to provide a conceptual overview of trade deficits, tariffs, and the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency role. We conclude with potential scenarios for how trade policy and the economy will consequently play out.

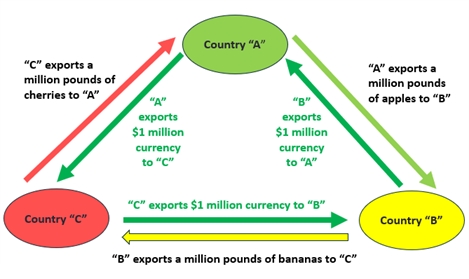

Imagine a simple world economy, consisting of exactly three countries of comparable demographics and economic output. Each country is entirely self-sufficient, save for one industry—produce. Because of the varying characteristics of their soils, each country has a decided advantage in growing a particular type of fruit. However, the consumers in each country prefer the taste of fruit that grows faster and larger in one of the other two countries.

For simplicity’s sake, we’ll assume that each country exports the same amount of fruit (in pounds), each pound of fruit costs the same, and that all payments are settled in the same currency, which we’ll conveniently call “dollars.” Country “A” exports a billion pounds of apples to Country “B,” which in turn, exports a billion pounds of bananas to Country “C.” For its part, Country “C” sends a billion pounds of cherries to Country “A.”

Of course, no country is going to willingly export all its fruit production and receive nothing in exchange. So “B” sends “A” a billion in currency, “C” does the same to “B,” while “A” sends “C” a billion dollars. Consequently, each country is in a trade deficit (net dollar export) with one trading partner and in a trade surplus (net dollar import) with another trading partner. In aggregate, however, each country has no net trade deficit.

Because the consumers derive greater satisfaction from eating imported, rather than home-grown, produce, they’re collectively happy with this “triangular trade” arrangement—trade deficits notwithstanding.

From the 16th to the 18th centuries, countries with trade deficits were often considered as ‘losing’ to their trading partners due to the attendant net payment outflows (typically made in gold and silver). Conventional wisdom held that the best method to increase a nation’s wealth was to levy high tariffs on goods imported from other countries, thereby minimizing imports and maximizing the net inflow of precious metals made in payment.

Opposing this “mercantilist” school of economic thought, Scotsman Adam Smith published a landmark book in 1776—The Wealth of Nations. In its pages, Smith argued that a focus on gold and silver was a flawed measure of national wealth. Rather, the true measure of wealth is the “annual produce of the land and labor of the society.” Accordingly, more free trade implied a greater division of labor, which meant higher productivity and greater total wealth.

In Smith’s view, tariffs were generally undesirable. By disrupting the natural flow of trade, resources were prevented from flowing to their most efficient uses. Tariffs raised the prices of imported goods, leading to higher costs for consumers and businesses alike. The reduced international competition also frequently led to complacency and inefficiency among domestic producers.

Although he was broadly opposed to tariffs, Smith did recognize a few situations where they might be justified. In particular, he believed that tariffs could be legitimately used to protect industries that were integral to national defense (e.g., shipbuilding). A country might also consider levying a tariff to incentivize another country to remove tariffs that it had previously imposed. Unfortunately, such retaliatory strategies often backfired as they escalated into trade war, resulting in lower total production and consumption for everyone.

Nearly 250 years after The Wealth of Nations was published, the United States finds itself facing similar questions about free trade, tariffs and national security. On one hand, economists of all stripes generally agree that rising levels of free trade have broadly increased consumer prosperity across the world. On the other hand, globalization has upended U.S. producers in many industries and the integration of global supply chains has raised legitimate national security concerns.

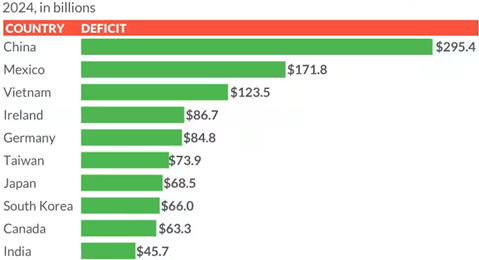

Since at least the late 1980s, President Donald Trump has embraced an American mercantilist worldview. Initially, he railed against large trade deficits with Japan, but more recently, China has become the primary target of his rhetoric. In the latter case, a growing military rivalry may be a larger concern than the $295 billion U.S.–Chinese trade deficit.

Source: U.S Census and Bureau of Economic Analysis

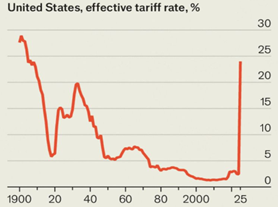

Trump’s first term was marked by an array of protectionist measures, notably against China. As his second term commenced, he implemented further tariffs, which were largely in line with the expectations of markets and politicos. However, the method and magnitude of “Liberation Day” tariffs on April 2nd were more haphazard and larger than anyone anticipated. The average U.S. tariff rate is set to rise to levels not seen in 100 years—even higher than the infamous Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, whose implementation exacerbated the Great Depression.

Trump’s so-called “reciprocal tariffs” plan assigns a levy on about 90 countries, calculated at a rate of half of the U.S.’s trade deficit with a foreign country, divided by that country’s exports to the U.S. Even for countries with no trade deficit with the U.S., like Australia, a baseline 10% tariff will still be applied.

For example, because of its $123 billion trade surplus with the U.S., Vietnam will now face a 46% tariff rate. Vietnamese officials have responded by offering to reduce their small import duties to zero, but White House trade advisor Peter Navarro indicated that the concession was insufficient. “Zero tariffs…means nothing to us because it’s the nontariff cheating that matters.” Navarro cited examples of Chinese products being routed through Vietnam, intellectual property theft and value-added tax on goods.

Negotiations with Vietnam present a rather troublesome case. Vietnam is the U.S.’s tenth-largest trading partner and is an integral link in the global supply chain for major manufacturers, including Apple, which produces 20% of its iPads, and Nike, which manufactures 50% of its goods in the country. The lofty 46% tariff rate doesn’t appear to be primarily driven by military concerns or a desire to reduce existing tariffs. Rather, the goal seems to be slashing a trade deficit with a major trading partner. If that is indeed the primary aim of the new tariff regime, then turbulent economic conditions are all but assured for coming months.

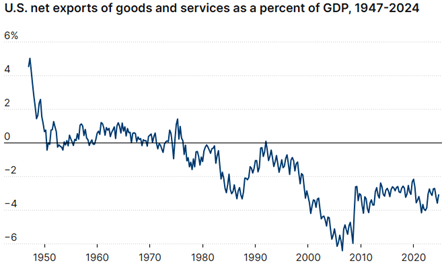

It’s difficult to precisely model the effects of trade on the U.S. economy. At a superficial level, the total value of imports and exports as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP) is roughly 25%. As exports are 11% and imports are 14%, the U.S. runs a trade deficit of about 3% annually. (The value of services is also included in most of the reported calculations.)

Source: The Brookings Institution

Since 1975, the U.S. has consistently run a net trade deficit in every calendar year. For most countries, economic theory would dictate that this exchange of a domestic currency for foreign goods and services would depress the currency’s value against foreign currencies. Over time, the declining currency value would make domestic goods appear cheap to foreign buyers and the trade deficit would self-remedy. But because of the U.S. dollar’s reserve currency status, the general rules don’t apply.

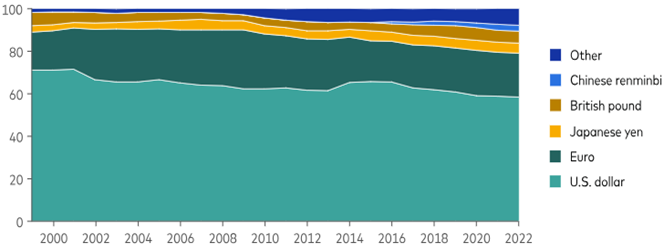

As a reserve currency, the dollar is a linchpin of both world trade and the global financial system. Payments for exports and imports are settled in dollars. Funds are loaned and borrowed in dollars, and the prices for important commodities (such as crude oil) are set in dollars all over the world. The euro, Japanese yen, British pound and Chinese renminbi also serve as reserve currencies, but to a much lesser degree. As a percentage of foreign exchange reserves, the U.S. dollar commands an impressive 60% market share.

Share of Foreign Exchange Reserves

Source: Vanguard Group

The dollar’s reserve currency status is a primary reason that the U.S. consistently runs trade deficits. One of our largest—and most important—exports is dollar-denominated financial assets (like Treasury bills). If the U.S. somehow managed to start running a net trade surplus, the rest of the world would soon be starved for dollars. There’s simply no way for the U.S. to consistently run a net trade surplus (or even run at breakeven) without the dollar concurrently losing reserve currency share.

On the surface, the “reciprocal tariffs” appear to be an amateurish approach to undoing the U.S.’s consistent trade deficits. However, they may ultimately serve as a segue into a broader conversation regarding the dollar. Trump’s preferred endgame may be a coordinated devaluation of the dollar against other currencies, reminiscent of the “Plaza Accord” of 1985.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection began enforcing new country-specific “reciprocal” tariffs at midnight on Wednesday, April 9th. Later that day, President Trump announced a 90-day pause on all reciprocal tariffs, with one exception; tariffs on China will be increased to 145% from 104%. China responded by raising its own tariff on U.S. goods to 125%. Then on late Friday, April 11th, U.S. Customs and Border Protection published several exemptions from the tariffs, notably smartphones, computers and other electronics.

The 10% universal tariff on all trading partners that went into effect on April 5th will remain in place. (Notably, Canada and Mexico have been exempted from the 10% provision, although auto exports, steel, and aluminum are subject to separate tariffs.)

We envision three scenarios for how trade policy and the economy will likely play out from here:

Scenario 1) Trump Folds Due to Economic and Political Pressure

Economists, CEOs, Wall Street luminaries, and even DOGE chief Elon Musk have warned President Trump that the tariffs will have adverse effects on corporate earnings and employment, with current increases in consumer prices. And volatile stock and bond markets are barking a similar message.

Trump, for his part, has acknowledged the interim discomfort to his plan: “I don’t want anything to go down, but sometimes you have to take medicine to fix something.” At some point, though, enough patients collectively screaming at the physician about miserable side effects could impel him to abandon the prescription.

Scenario 2) Trump Wins “Bigly” in a “Mar-a-Lago Accord”

Forty years ago, representatives of the U.S., France, Germany, UK, and Japan convened at the Plaza Hotel in NYC, collectively agreeing to devalue the U.S. dollar and thereby reduce the U.S. trade deficit. Stephen Miran, Trump’s appointed Chair of the Council of Economic Advisers of United States, outlined a comparable plan last November.

Miran’s treatise, A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System, outlines an approach to America’s chronic trade deficit / world reserve currency dilemma. He advocates trading partners to revalue their currencies (upward against the USD) and increase industrial investments in the U.S. Miran acknowledges that while tariffs can be used as temporary measures to initiate negotiations, large-scale retaliatory measures from trade partners could undermine the currency valuation dialogue.

To put it mildly, the economic world has evolved since 1985. At the time, the U.S. economy was three times as large as runner-up Japan’s. The largest European economy, West Germany, was about 30% the size of the USA’s. Today, European countries now negotiate as a 27 member-state block comprising the world’s second-largest economy (about -30% smaller than the U.S.). China’s economy is of comparable size and governed by a one-party communist state. Combined, the EU and Chinese economies are 35% larger than the United States’. Their collective muscle gives them much more power at the trade bargaining table than their predecessors enjoyed in the Reagan years.

Scenario 3) 10% Baseline Tariffs and Protracted Trade War with China

For the past four-and-a-half decades, nations around the world have increasingly moved towards a globally integrated economic model, which enabled greater division of labor, higher output, and downward pressure on prices. A reversal of that dynamic implies the opposite: less labor specialization, lower output, and an increased price level (though not necessarily higher recurring inflation).

Even with the delay or removal of “reciprocal tariffs” on every country barring China and tariff waivers for Canada and Mexico (America’s two largest trading partners), roughly 57% of America’s imports would still be subject to a 10% baseline tariff. The 13% of American imports coming from China would be subject to a 145% tariff. Yale Budget Lab currently estimates that American consumers will now face overall average effective tariff rate of 27%, the highest level since 1903.

Source: The Economist

Last October—before the reciprocal tariffs were announced—Yale University’s Budget Lab modeled the effect of a 10% broad tariff and 60% Chinese tariffs, assuming no retaliation. The Lab concluded that consumer prices would rise by +1.4% to +5.1% before product substitution effects, with a concurrent real GDP decline of -0.5%. to -1.4%. At a 22% average effective tariff rate, Apollo Group projects a -1.5% impact on GDP and +1.5% on inflation.

Lighthouse’s Assessment

China’s nominal GDP was roughly $19 trillion in 2024. Roughly 1.6% of that figure represents its net exports to the United States. For its part, America’s net imports from China reduced its $29 trillion GDP by about 1%. So, while neither party would economically stand to benefit from a trade war, it seems possible that such a conflict could be waged without inducing a severe recession in either country.

Trump’s 30+ years of mercantilist views and consistent anti-Chinese rhetoric lead us to believe that he’s willing to endure both low-single-digit GDP growth and a comparable one-time jump in consumer prices to achieve his goal of attenuating Sino-American trade imbalances. The fact that the 10% universal tariffs on all trading partners (barring Canada and Mexico) are set to remain in place, despite the postponement of the “reciprocal tariffs,” also augurs reduced economic growth.

As much as we’d like to see the recent drawdown in stocks as a great buying opportunity, the simple fact is that U.S. stocks are still quite expensive, particularly in light of this tariff-driven slowdown. Approximately 42% of the S&P 500’s revenue derives from overseas; for the “Magnificent Seven,” the figure is over 50%. And given the likelihood of higher consumer prices and the Federal Reserve’s insistence on lower inflation figures before additional rate cuts are made, The Fed doesn’t seem to be waiting in the wings to buttress stock prices.

Our mild economic pessimism is based on American and Chinese trade policies as they stand as of 4:00 p.m., April 15th, 2025. Given the manic pace at which policy has been changing, it’s possible that our views could shift considerably over the next few days or weeks. We emphasize that an impending trade war does not justify panic selling of any asset class. However, we do believe that fundamentals and valuations both warrant keeping stock exposure on the lower side of tactical risk allocations.

Please reach out to us if you would like to discuss capital markets or your personal financial plan.

Teancum D. Light, JD, CPA, CFP®

Teancum D. Light, JD, CPA, CFP®

President

Chief Investment Officer

Disclosures: This material is for informational purposes only and is not rendering or offering to render personalized investment advice or financial planning. This is neither a solicitation nor a recommendation to purchase or sell an investment and should not be relied upon as such. Before taking any action, you should always seek the assistance of a professional who knows your particular situation for advice on taxes, your investments, the law or any other matters that affect you or your business. Although Lighthouse Wealth Management has made every reasonable effort to ensure that the information provided is accurate, Lighthouse Wealth Management makes no warranties, expressed or implied, on the information provided. The reader assumes all responsibility for the use of such information.